Fukushima Wastewater Release: Japan’s Plan to Pump Contaminated Water Into the Ocean Explained

Published on February 6, 2026 by Dr. Ahmad Mahmood

Introduction: Why Fukushima’s Wastewater Plan Still Matters

More than a decade after the Fukushima nuclear disaster, Japan’s decision to release treated radioactive wastewater into the Pacific Ocean remains one of the most closely watched environmental issues in the world. The Fukushima wastewater release is not a single event but a multi-decade process with global environmental, political, and public trust implications.

While Japanese authorities argue the release is scientifically safe, critics question long-term risks, cumulative impacts, and whether enough transparency exists for a decision of this scale.

Background: What Happened at Fukushima Daiichi

In March 2011, a massive earthquake and tsunami triggered meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, operated by Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO).

To prevent further overheating, enormous quantities of water were used to cool damaged reactors. This water became contaminated after coming into contact with melted nuclear fuel and radioactive materials.

What Is the Contaminated Water?

How the Wastewater Accumulated

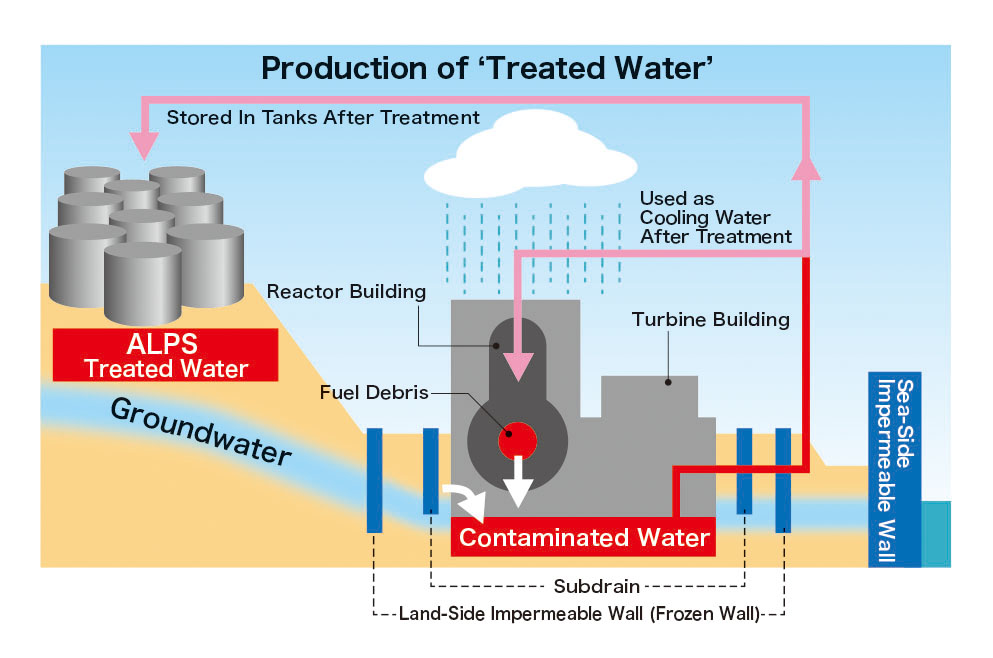

The contaminated water consists of:

- Cooling water used on damaged reactors

- Groundwater seeping into reactor buildings

- Rainwater mixing with contaminated areas

After treatment, the water has been stored in over 1,000 large tanks at the site, occupying valuable space needed for decommissioning.

What Is Japan’s Wastewater Release Plan?

Japan’s government approved a plan to gradually discharge treated wastewater into the Pacific Ocean, diluted to meet international safety standards. The release is expected to continue for 30 to 40 years.

Timeline and Current Status

The discharge process began in phases after regulatory approval, with ongoing monitoring and public reporting. Each release batch is tested before dilution and discharge.

The ALPS Treatment System Explained

The Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS) removes most radioactive isotopes from the wastewater.

What ALPS Removes — and What It Doesn’t

ALPS can reduce dozens of radionuclides to below regulatory limits. However, it cannot remove tritium, a radioactive form of hydrogen that becomes chemically inseparable from water.

Tritium: The Most Controversial Element

Tritium emits low-energy radiation and is routinely released in small quantities by nuclear facilities worldwide. Japanese authorities argue that diluted tritium levels will be far below international safety thresholds.

However, critics argue that:

- Long-term cumulative effects are uncertain

- Tritium can bind with organic matter

- Public trust has been damaged by past nuclear mismanagement

Environmental and Marine Ecosystem Concerns

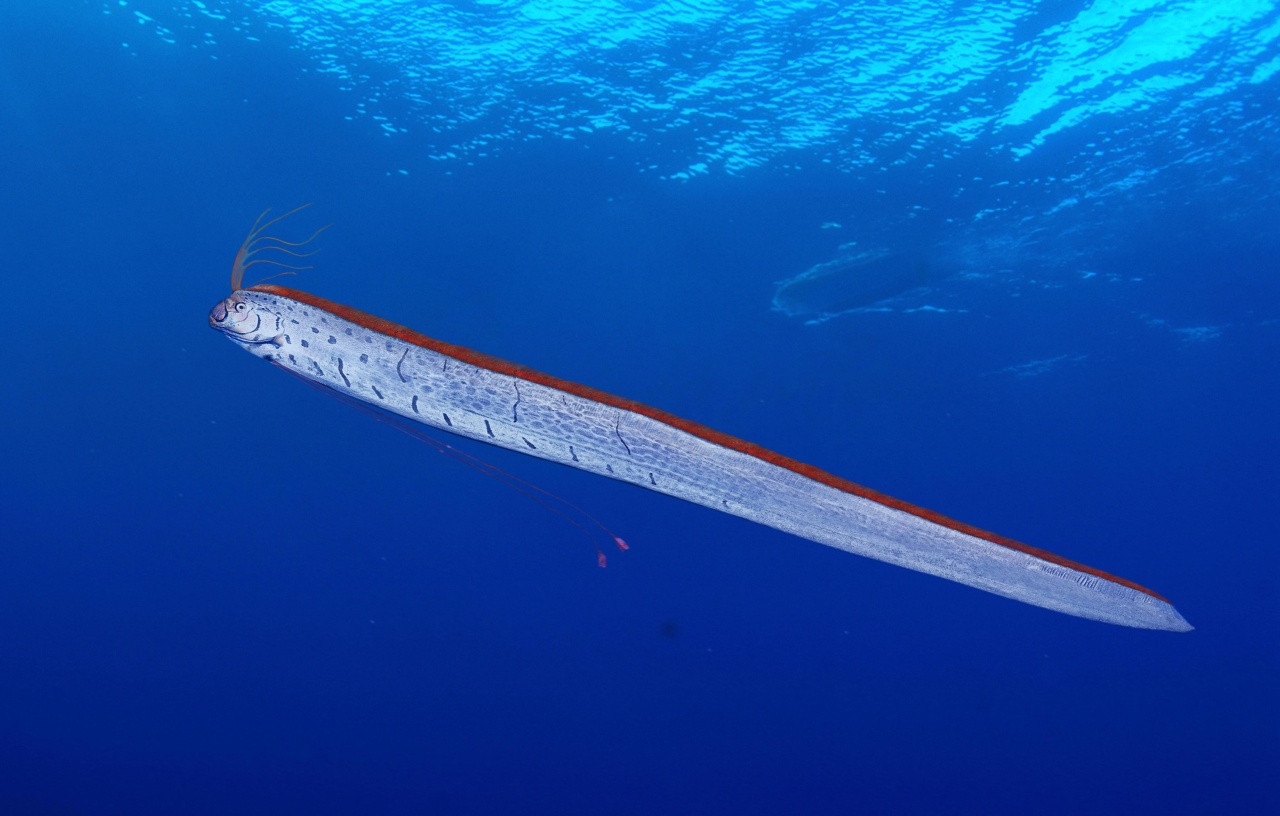

Marine scientists note that while immediate impacts may be low, concerns remain about:

- Bioaccumulation over time

- Effects on plankton and fish larvae

- Combined stressors like climate change and pollution

Fishing communities fear reputational damage even if contamination levels remain low.

Human Health Risk Assessment

According to assessments reviewed by the International Atomic Energy Agency, projected radiation exposure from the release is negligible compared to natural background radiation.

Public health experts emphasize that risk perception, not just radiation dose, plays a major role in social impact.

International Reactions and Geopolitical Tensions

Several neighboring countries have raised objections, citing:

- Insufficient consultation

- Transboundary environmental risk

- Lack of trust in monitoring

In response, Japan has pledged transparency and allowed international observers.

What Global Nuclear and Environmental Authorities Say

The IAEA has stated that Japan’s plan is consistent with international safety standards, while also emphasizing the importance of continuous monitoring and data disclosure.

Environmental organizations remain divided, with some calling for alternative disposal methods and others focusing on the precedent this sets for future nuclear accidents.

Why the Decision Remains Controversial

The controversy is not purely scientific. It also reflects:

- Historical trauma from nuclear disasters

- Unequal risk perception among coastal communities

- Broader concerns about ocean protection

Once released, the wastewater cannot be retrieved, making the decision effectively irreversible.

Alternatives Considered — and Rejected

Japan evaluated other options, including:

- Long-term storage

- Underground burial

- Evaporation

Each was deemed impractical due to safety risks, land constraints, or environmental concerns.

Long-Term Monitoring and Transparency

Japan has committed to:

- Real-time radiation monitoring

- Open data sharing

- Independent international verification

Long-term trust will depend on whether these commitments are upheld consistently.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the Fukushima wastewater radioactive?

Yes, but most radionuclides are removed, leaving primarily tritium.

Is tritium dangerous?

At low concentrations, risk is considered minimal, but uncertainty remains.

Will this affect seafood safety?

Authorities say no measurable impact is expected, but monitoring continues.

Why not store the water forever?

Space, safety, and decommissioning needs limit storage options.

Who oversees the release?

Japanese regulators with international oversight from the IAEA.

How long will releases continue?

Several decades.

Conclusion: Science, Trust, and Long-Term Responsibility

The Fukushima wastewater release represents a complex intersection of science, environmental stewardship, and public trust. While technical assessments suggest low immediate risk, the long-term legacy of the decision will depend on transparency, monitoring, and respect for global concerns.

In a world already facing ocean warming, pollution, and biodiversity loss, Fukushima serves as a reminder that environmental decisions extend far beyond national borders.