Table of Contents

ToggleTackling Carbon Leakage in a Global Economy

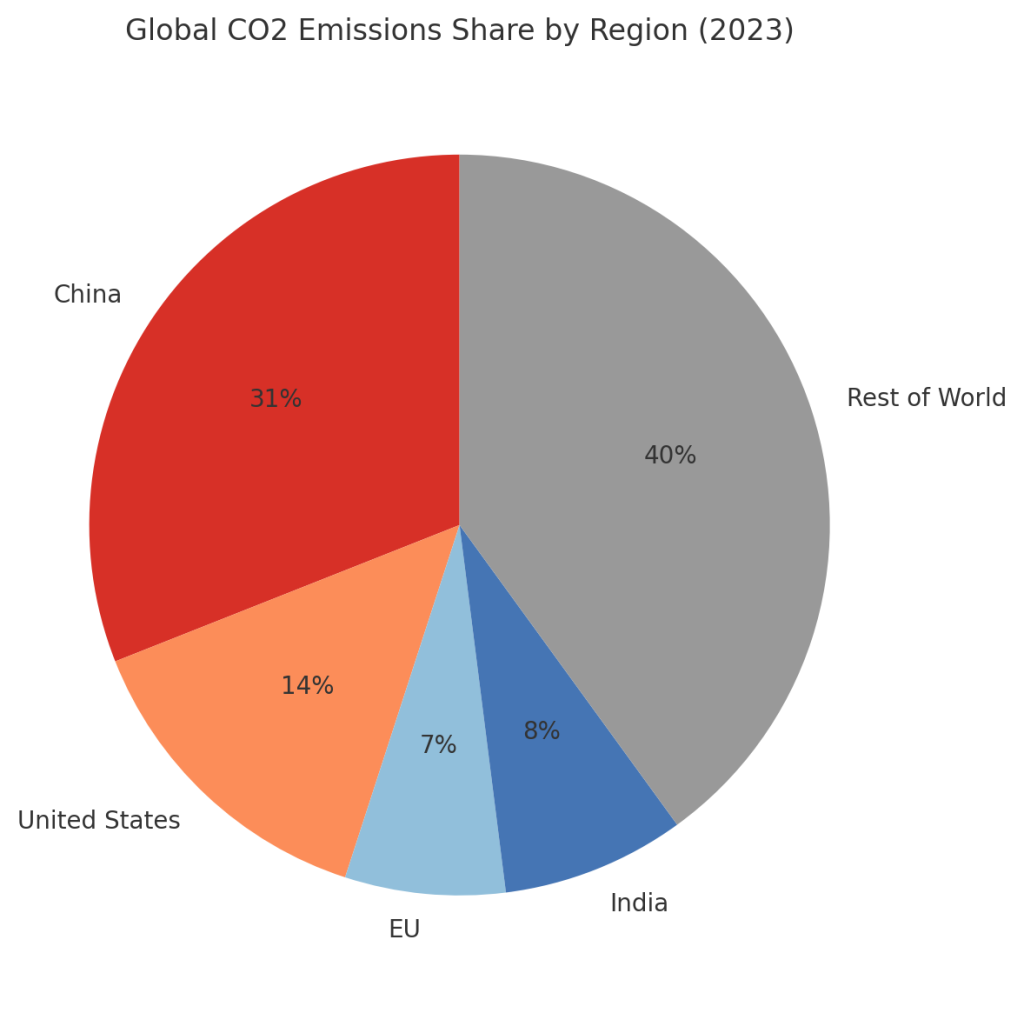

Global Carbon Emissions Imbalance: China alone accounts for about 31% of global CO2 emissions, while the United States contributes ~14%, and the EU about 7%. Climate change is a global problem, and unilateral efforts can be undermined if carbon-intensive production simply shifts to regions with looser standards. This phenomenon, known as carbon leakage, occurs when emissions are not actually cut but just move elsewhere along with industrial activity. The EU’s answer to this challenge is the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) – a policy tool designed to put a fair price on the carbon content of imported goods and prevent the offshoring of pollution. In a conversational journey through CBAM, we’ll explore its purpose, how it works as part of the EU Green Deal, its link to climate change mitigation, the controversies it sparks, and how it compares to similar ideas worldwide.

Unpacking CBAM: What It Is and Why It Was Introduced

What exactly is CBAM? At its core, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is essentially a carbon tariff on certain imports into the EU. It charges importers for the greenhouse gas emissions embedded in carbon-intensive products coming from countries with less stringent climate policies. In simpler terms, if a foreign manufacturer didn’t have to pay for its carbon pollution back home, the EU will make them pay at the border. This “leveling the playing field” ensures that European companies – who already pay for carbon emissions under the EU’s carbon pricing system – aren’t undercut by cheaper, high-carbon imports. By equalizing carbon costs, CBAM aims to remove the incentive for companies to relocate production to countries with lax climate rules, thereby addressing carbon leakage and protecting the integrity of EU emissions cuts.

Why did the EU introduce CBAM now?

The mechanism is a pillar of the EU’s ambitious climate agenda. Under the European Green Deal’s “Fit for 55” package, the EU committed to cut greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 (from 1990 levels) and reach net-zero by 2050. Achieving these targets involves tightening the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) – effectively raising carbon costs for EU industries. But without a border adjustment, there was a real fear that EU industries like steel, cement, and fertilizers would lose out to foreign competitors not bearing similar costs, or worse, shift production (and emissions) abroad. CBAM was conceived to “mirror” the EU’s carbon price on imports of these goods, ensuring the EU’s climate efforts aren’t undermined by imported emissions In essence, CBAM is both a climate tool and a trade measure: it reinforces the EU’s climate leadership by extending carbon pricing beyond its borders, while also nudging other countries to adopt greener practices to maintain access to the EU market.

How Does the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism Work?

Implementing CBAM involves a step-by-step process and a transition period to ease into this new system. Here’s a breakdown of how it works:

Covered sectors and emissions reporting: In its initial scope, CBAM applies to imports of highly carbon-intensive goods: iron and steel, cement, aluminum, fertilizers, electricity, and hydrogen, as well as some downstream metal products. These are sectors at high risk of carbon leakage. During a transitional phase (October 2023 through 2025), importers of these goods must report the embedded emissions in their imports on a quarterly basis. They don’t have to pay a financial adjustment yet in this phase, but they’re learning how to calculate and declare the carbon footprint of their goods – essentially a pilot period to gather data and refine methodologies.

CBAM certificates and pricing: Once the system is fully operational (from 2026 onward), importers will need to purchase and surrender CBAM certificates for the volume of CO2 emissions embedded in their imported goods. The price of these certificates will be pegged to the EU carbon price. In practice, this means if the EU ETS price is, say, €85 per ton of CO2, an importer bringing in 1 ton of steel that emitted 1 ton CO2 during production would need to pay €85 (1 certificate) to cover those emissions. If the foreign producer already paid a carbon price at home, the EU will grant a deduction – you only pay the difference so as not to double-charge. Each year, importers must declare the total emissions of that year’s imports and surrender the equivalent number of certificates. By aligning the cost of carbon for domestic and imported products, CBAM ensures everyone pays for their pollution in the same way.

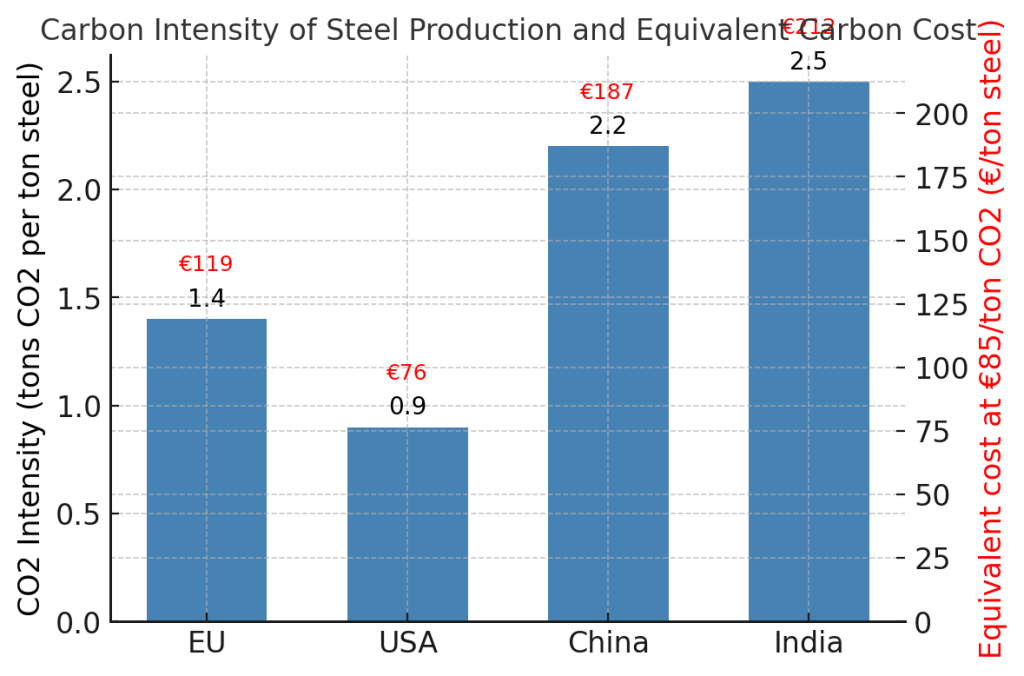

Carbon Intensity and Cost Impact: One reason CBAM focuses on basic materials like steel is the large variation in carbon intensity across countries. For example, Chinese steelmakers on average emit about 2.3 tons of CO2 per ton of steel – significantly higher than the global average (around 1.4 tons). In contrast, U.S. and European steel production tends to be cleaner per ton, partly due to greater use of electric arc furnaces recycling scrap (about 70% of U.S. steel is made from scrap in EAFs). The chart above compares estimated CO2 emissions per ton of steel in the EU, USA, China, and India, and shows the equivalent cost if a carbon price of €85/ton were applied. If an importer brings in steel from a higher-emissions source, they would pay a higher border fee (e.g. over €180 per ton for Chinese steel vs ~€120 for EU steel) to account for that difference. This mechanism incentivizes foreign producers to clean up their processes or else pay the price at the EU border.

Transitional phase vs. full implementation: During the 2023–2025 transition, importers only have reporting obligations – a period to adjust and gather emissions data. Starting 1 January 2026, the system enters into force financially: importers must purchase CBAM certificates for emissions of covered imports. CBAM is being phased in gradually in lockstep with the phase-out of free allowances under the EU ETS. EU industries have long received some free carbon permits to shield them from foreign competition. Now those free allowances for CBAM-covered sectors will be reduced year by year from 2026 until they reach zero by 2034. In other words, as domestic producers lose their free carbon protection, the border tariff ramps up equivalently. This avoids double protection and complies with WTO rules by not over-sheltering EU firms. By 2030, free allocations will be roughly halved, and by 2034, CBAM will entirely replace the free permit system.

Timeline: The EU will phase out free emission allowances for industries (yellow line) as it phases in CBAM charges on imports (red line). In 2026, EU importers will face CBAM costs for only ~2.5% of emissions (97.5% still covered by free allowances), but by 2030 the CBAM will cover nearly half the emissions, and by 2034 it will cover 100%, as free allowances drop to zero. This gradual schedule gives industries time to adapt while fully aligning importers with the EU’s carbon price.

CBAM’s Role in the European Green Deal

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is a key component of the EU’s Green Deal and its broader climate strategy. It was formally proposed as part of the “Fit for 55” legislative package in July 2021, which itself is the roadmap to achieve the EU’s Green Deal goals. By enforcing carbon costs on imports, CBAM directly supports the EU’s plan to cut emissions 55% by 2030. Here’s how it fits in:

- Supporting domestic climate ambition: The EU is strengthening its internal carbon pricing (EU ETS) – raising costs for power plants, factories, and other emitters within Europe. CBAM complements this by ensuring that emissions aren’t simply outsourced. It gives the EU confidence to ambitiously tighten its ETS caps without fear that domestic industries will be undercut by foreign competitors who don’t pay equivalent carbon costs. In effect, CBAM is a guardrail for the Green Deal: it prevents “carbon leakage” from undermining Europe’s emission reductions. This means European climate policies can be more stringent, knowing that imports will face comparable costs.

- Driving global action through example: The EU Green Deal isn’t just inward-looking; it aspires to leadership in global climate action. By implementing CBAM, the EU sends a strong signal globally that carbon-intensive trade has a price. Already, other nations are watching closely or planning their own measures (as we discuss later). The mechanism thus nudges trading partners toward considering carbon pricing or cleaner production to maintain market access. In the grand scheme, CBAM is one of the Green Deal’s tools to mainstream climate considerations into all policy areas, including trade. It aligns trade policy with climate goals – a novel move that other green deals or climate strategies globally are likely to contemplate as well.

- Revenue for climate and transition: While not the primary goal, CBAM will generate revenue (from the sale of certificates). The EU has signaled that these funds could be used to finance climate-related projects or assist poorer countries’ decarbonization – reinforcing the Green Deal’s spirit of a just transition. (Though as of now, the exact allocation of CBAM revenues is still being debated, with many developing nations urging that it be channeled to help them comply and cut emissions.)

In summary, CBAM fortifies the EU Green Deal by protecting its emission reductions and incentivizing broader international cooperation. It operationalizes the principle that climate ambition at home should not lead to job losses or emission exports abroad, thereby marrying environmental integrity with economic fairness – a cornerstone concept of the Green Deal.

Linking CBAM to Climate Change Mitigation

How does a trade tariff help fight climate change? The link might not be obvious at first, but CBAM is fundamentally about reducing global emissions, not just EU emissions. It tackles a critical gap: under the Paris Agreement, countries have uneven climate targets and carbon prices. This creates an economic loophole where emissions can simply shift locations. CBAM seeks to close that loophole by ensuring the EU’s market rewards lower-carbon production globally.

Firstly, CBAM directly targets the reduction of embodied emissions in goods. By putting a price on the carbon content of imports, it encourages cleaner production methods abroad. For example, a steel mill in Country X might invest in efficiency or switch to cleaner energy if it means avoiding a hefty tariff when selling to Europe. Over time, this can drive down emissions in those exporting countries – effectively extending the reach of EU climate policy beyond its borders. In this way, CBAM acts as a catalyst for climate change mitigation internationally, leveraging the EU’s market power to promote greener practices elsewhere.

Secondly, CBAM helps maintain public and political support for strong climate action in the EU. If European industries were simply outsourcing emissions and jobs to other countries, it could erode the domestic consensus for policies like the EU ETS. By remedying carbon leakage, CBAM ensures that EU emissions cuts deliver real global climate benefits, not just local reductions offset by rises elsewhere. This integrity is crucial for the credibility of EU climate leadership. It also resonates with the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” – all countries should contribute to emissions reduction, but mechanisms can be put in place to account for different capabilities. CBAM in effect asks foreign producers to either clean up or pay up, which some argue is a way to prod wealthier countries or major emitters to do more, in line with climate responsibilities.

That said, CBAM is not a silver bullet for climate change. It covers specific sectors and is one piece of a much larger puzzle. Its true impact on global emissions will depend on how trade partners react – ideally by adopting their own carbon pricing or cleaner tech (a win-win), rather than by engaging in trade disputes. There’s evidence that the mere prospect of CBAM has already prompted conversations in countries like China about measuring and curbing industrial emissions. From a climate mitigation perspective, this is exactly the kind of domino effect the EU hopes for: a race to the top in climate standards rather than a race to the bottom.

In summary, CBAM ties into climate change mitigation by ensuring that ambitious climate action isn’t undermined by global trade dynamics. It extends the carbon accountability to imported goods, thereby promoting emission reductions beyond the EU’s territory. If scaled up or adopted by multiple major economies, carbon border adjustments could become a powerful tool to drive worldwide emissions down while preventing “leakage” – aligning global trade with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Impact of CBAM on Industries and Trade

CBAM’s introduction is reshaping the landscape for certain industries and international trade flows. For European industries in covered sectors (steel, aluminum, cement, fertilizers, electricity, etc.), the mechanism is often seen as leveling the competitive field. These companies will progressively lose their free CO2 allowances and have to pay for all their emissions under the EU ETS – but they gain protection in that competitors exporting to the EU must pay an equivalent carbon cost. In theory, this removes any unfair advantage a foreign producer might have from operating under lax environmental policies. European producers can compete more on innovation and efficiency rather than who faces a carbon price and who doesn’t.

From an industry perspective, CBAM could drive innovation. By attaching a monetary cost to carbon emissions for imports, it rewards cleaner production methods. Sectors like steel and cement are energy-intensive and historically hard to decarbonize. With CBAM, a producer (be it in the EU or abroad) that invests in green technology (like green hydrogen for steel or alternative cements) will have a cost advantage in the EU market over a high-emission producer. We may see accelerated investment in low-carbon processes, not just in Europe but globally, to maintain market share. In the long run, CBAM could stimulate a market for “green” materials, where steel or cement with lower embodied carbon is in demand to avoid tariffs. It’s a bold experiment in using trade policy to push industrial decarbonization.

For international trade, the immediate impact of CBAM will be on countries that are major exporters of the covered goods to Europe. Countries like Russia (steel, fertilizers), China (steel, aluminum), Turkey (steel), Ukraine (iron, steel, fertilizer), and others have been identified as having significant exposure to the EU market under CBAM. Some of these exporters may lose a bit of price competitiveness in the EU if their production is carbon-heavy and they face the full adjustment cost. We might see trade flows adjust; for instance, cleaner producers might expand their share of EU imports, while dirtier producers either improve or seek alternative markets. Importers in the EU could also start switching to sourcing from countries with lower carbon footprints to reduce the number of certificates they must buy.

There’s also a potential upside for developing cleaner economies: if a country has a low-carbon electricity grid or modern efficient factories, it could market its exports as “CBAM-friendly” with lower added costs. In this way, CBAM can create a differentiation based on carbon intensity. Some emerging economies that invest early in clean tech might actually become more competitive in the EU market than their higher-emitting rivals.

Of course, these shifts won’t happen overnight. CBAM is being phased in gradually, and initially the costs will be limited (especially during the reporting-only transition period). The EU hopes this gradualism gives everyone time to adjust. European importers will be learning how to measure emissions of their supply chains; foreign producers will learn how to report or reduce them. The true trade impacts will start to bite in the late 2020s as free allowances wane and real payments ramp up.

One concern for EU industries is how exports will be treated. CBAM currently addresses imports into the EU, but what about EU manufacturers exporting abroad who face EU carbon costs that competitors outside don’t? There’s no rebate for carbon costs on exports (WTO rules make that tricky). This could make EU goods pricier in foreign markets. The EU is aware of this and is banking on other countries raising their climate ambition over time. In the meantime, some industry groups worry about being at a disadvantage abroad. This remains a point of discussion – whether future adjustments or agreements might account for carbon costs in exports.

In summary, CBAM is poised to impact industrial competitiveness and trade patterns by embedding carbon costs into the price of goods. It’s likely to advantage cleaner producers and push carbon-intensive ones either to improve or face shrinking export markets. As such, it’s a grand experiment in aligning trade with climate objectives, and its real-world impacts will be closely watched by industries and policymakers worldwide.

Criticisms and Challenges of CBAM

No bold policy comes without controversy, and CBAM is no exception. Critics range from trading partners and global development advocates to industry voices and trade experts. Here are the major challenges and critiques leveled at the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism:

Trade tensions and WTO concerns: Implementing a carbon tariff risks friction with international trade partners. Some countries view CBAM as a protectionist tool in green disguise, suspecting the EU of shielding its industries under the pretext of climate action. Notably, Russia, China, and some emerging economies have voiced strong objections. They argue CBAM could unfairly impede their access to the EU market. A key question is whether CBAM complies with World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. The EU insists it has designed CBAM to be WTO-compatible – treating all imports equally based on carbon content and mirroring the cost EU firms already bear (thus not an arbitrary discrimination). However, WTO compliance could ultimately be tested via disputes. If CBAM is perceived as violating WTO’s non-discrimination principles, we could see challenges. The diplomatic reaction so far has been mixed: some countries are considering their own carbon pricing in response, while others have hinted at possible retaliatory tariffs if they deem CBAM punitive. This delicate balance – encouraging climate action without sparking a trade war – is one of CBAM’s biggest challenges.

Equity and impact on developing countries: Perhaps the most profound criticism comes from a climate justice perspective. Developing countries worry that CBAM penalizes them for historical emissions they didn’t cause and for not having the financial or technical means to decarbonize quickly. They see it as the rich world shifting the burden onto poorer nations. As one analysis put it, CBAM appears to go against the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” under the UN climate regime, which recognizes different capabilities and responsibilities between developed and developing nations. For example, countries in Africa or South Asia that export basic materials could be hit by the EU’s carbon fee even though their per-capita emissions are low and they’ve contributed little to climate change historically. This raises issues of fairness: is it right for the EU to collect revenue on emissions in other countries? What about the idea that developed nations should support, not punish, developing countries in green transitions? These concerns have led to calls for exemptions or financial support. Some suggest CBAM revenues should be redirected to help poorer producers green their processes, as a form of climate finance. The EU has not exempted any country by default (beyond those with equivalent carbon pricing), but it has floated partnerships and aid to affected trading partners. Still, the perception of CBAM as an “external imposition” on developing countries risks undermining goodwill. It’s a tightrope between environmental effectiveness and equitable treatment.

Global cooperation vs. unilateral action: Climate change is a collective action problem, and some critics say CBAM could either undermine or enhance global cooperation – but the jury is out. On one hand, if seen as a punitive unilateral EU move, it might breed resentment and make international climate negotiations harder. On the other hand, defenders argue that CBAM is prodding laggards into action, effectively breaking the stalemate where some countries feared acting first. The optimal outcome would be other major economies adopting similar carbon pricing and perhaps forming a “climate club” with mutual carbon adjustments (something economists have suggested). A challenge here is getting everyone on the same page – the EU’s approach might not suit the U.S. or China politically, for instance. Until more countries implement their own carbon tariffs or prices, CBAM runs solo and faces the challenge of not becoming a new trade barrier that divides climate allies.

Administrative complexity: Another less glamorous but very real challenge is the nuts and bolts of making CBAM work. Measuring the carbon content of imported goods across different countries and production processes is complex. Importers will have to gather emissions data from overseas producers, which may have varying accounting methods or none at all. The EU will allow default values (based on the worst 10% of EU producers’ emissions) if importers can’t get precise data – meant as a deterrent for non-reporting. But verifying reports, preventing fraud (e.g. transshipment or slight product modifications to dodge CBAM), and managing the whole new bureaucracy of CBAM is a massive undertaking. Critics worry it could become a bureaucratic nightmare or that loopholes will be exploited. Small exporters might struggle with compliance costs. The success of CBAM will depend on robust monitoring, reporting, and verification systems. The EU has set up a central CBAM authority and a registry for importers, but it will be learning by doing in the first years. Any administrative failure or excessive red tape could undermine the policy’s credibility and effectiveness.

In summary, while CBAM is innovative, it must navigate a minefield of political, ethical, and practical challenges. Diplomatically, the EU needs to persuade partners that CBAM is a climate necessity, not green protectionism. It must address fairness concerns, possibly by recycling revenues or providing technical help to poorer nations. And it must build an efficient system to implement the policy. How these challenges are managed in the coming years will determine if CBAM becomes a new global standard or remains a contentious experiment.

Global Reactions and Similar Mechanisms Worldwide

The EU may be the first to implement a carbon border adjustment, but it certainly won’t be the last to consider one. CBAM’s ripple effects are already evident as other countries debate or design their own versions. Here’s a look at how key players are responding or planning similar mechanisms:

United States: Exploring a U.S. CBAM – In the U.S., talk of a carbon border adjustment has gained traction in policy circles, though the approach differs from the EU’s. The U.S. does not (yet) have a nationwide carbon price or ETS, making a classic CBAM trickier. However, lawmakers have proposed legislation to impose fees on carbon-intensive imports. Notably, the Clean Competition Act was introduced in Congress, aiming to create a U.S. carbon border adjustment that charges importers based on the carbon intensity of products. The idea is to start with a domestic benchmark: calculate the U.S. industry’s average emissions per unit for products like steel, aluminum, cement, etc., and then apply import fees on goods from countries with higher intensities. The bill proposed an initial carbon price (around $55/ton) rising over time. While this hasn’t become law, it shows a serious intent to follow the EU’s footsteps in principle. Additionally, the Biden administration has floated the concept of a “Climate Club” with the EU and other allies – essentially coordinating carbon tariffs or standards among a group of climate-ambitious countries. The U.S. domestic politics around climate tariffs are mixed: some industry groups worry about trade impacts, while others see an opportunity to penalize China’s high-emission industry and boost cleaner U.S. manufacturing. As of 2025, the U.S. has not implemented a CBAM, but it’s actively studying options. If the EU’s CBAM proceeds smoothly, it could strengthen the case for an American version, especially as a way to protect U.S. industries that are cleaner (on average) than their overseas competitors and to encourage global emissions cuts.

Canada: Carbon Tariff on the Horizon – Canada, which already has a robust domestic carbon price, has been closely considering a carbon border adjustment to complement its climate policy. The Canadian government held consultations on Border Carbon Adjustments (BCAs) in 2021, recognizing that as Canada’s carbon tax rises (it’s set to reach C$170/ton by 2030), domestic industries could face competitiveness pressures. Canadian officials have coordinated with the EU and even the U.S. (as per a 2021 joint statement) on addressing carbon leakage in trade. While Canada has not committed to a full CBAM yet, it is exploring designs that would suit its economy – possibly aligning with whatever the U.S. does to maintain North American consistency. Given Canada’s close economic ties to the U.S., a unilateral Canadian CBAM might be less likely unless the U.S. moves in tandem. That said, if the EU mechanism shows signs of success, Canada could implement a smaller-scale version, especially targeting imports of steel, cement, or electricity from countries with no carbon pricing. Canadian industry and experts largely support the idea as long as it’s WTO-compliant and doesn’t provoke major trading partners too harshly. In short, Canada is in “watch and prepare” mode, laying the analytical groundwork for a future CBAM if needed.

United Kingdom and other countries: The UK, having left the EU, is charting its own climate policy but often in parallel. The UK has its own ETS and has hinted at developing a UK CBAM in the next few years. In fact, the UK government announced plans to explore a CBAM and potentially implement one by 2026 or 2027 to protect UK industries and maintain parity with the EU’s policy. As one of Europe’s largest economies, the UK adopting a carbon adjustment would be a significant expansion of the concept. Other countries like Japan are studying the EU’s move, though Japan so far leans toward using trade diplomacy to encourage carbon reductions rather than immediate tariffs. Australia, under a previous government, criticized CBAM, but with a new pro-climate government, it is more open to mechanisms that could, for instance, favor its mineral exports produced with renewable energy. China has publicly criticized CBAM as unfair, yet internally it has begun pricing carbon (with a national ETS for the power sector) and is measuring emissions in industry, partly to be prepared for policies like CBAM. We might eventually see China or others develop their own border adjustments in response – although that may be a way off, as they currently focus on domestic measures.

In the broader sense, the EU’s CBAM is spurring a global conversation: should there be an agreed way to handle carbon in trade? Some propose an international carbon price floor for key industries or sectoral agreements (for example, a global steel agreement where major producers all impose a similar carbon cost). Another idea is linking up carbon markets – if more countries priced carbon similarly, there’d be less need for border adjustments. For now, the immediate future will likely see a patchwork: the EU leading, a few others like the UK, Canada possibly following, and big economies like the US and China engaging in careful calculations about the economic and diplomatic pros and cons. One thing is clear: the concept of carbon border adjustments has been injected into the global policy debate, and we can expect more countries to announce “CBAM-like” policies or alliances in the coming years, especially if climate ambition accelerates.

The Future of Carbon Border Policies

Looking ahead, the CBAM is just the first step into the uncharted territory of climate-aligned trade policy. Its success or failure will shape how the world approaches the nexus of trade and climate in the future. Here are some reflections on what the future might hold:

Expansion of CBAM (more sectors, more regions): By design, the EU’s CBAM will likely expand in scope over time. By 2030, the EU is contemplating adding more sectors – possibly chemicals, polymers, and other products covered by the EU ETS. If CBAM proves workable, the list of covered goods could grow until it mirrors the full breadth of carbon-priced activities in the EU. Geographically, we might see “CBAM clubs” emerge. Imagine a scenario where the EU, UK, Canada, possibly Japan or Korea, all have interoperable carbon border adjustment systems. They might recognize each other’s carbon prices (so trade between them wouldn’t need adjustments, focusing instead on imports from the remaining non-priced economies). Such alignment could reduce friction and also put more pressure on countries without carbon pricing to join the club or face multiple adjusted borders. In essence, CBAM could globalize — either through more countries adopting it or through international agreements that achieve a similar outcome (like a climate treaty on steel emissions).

Technological and data evolution: For carbon border measures to work long-term, we’ll need much better data on product carbon footprints. This means innovations in emissions accounting and transparency. We may see blockchain or digital product passports containing CO2 info for each batch of material. The future could involve automated systems where exporters attach verified emissions data to shipments. This might lower the administrative burden and increase accuracy. There’s a push for international standards on carbon accounting for products – if that matures, CBAM (and any other country’s version) becomes easier to implement and more fair. Technology could also help mitigate another risk: fraud or circumvention. Future systems might detect if, say, steel from Country A is rerouted through Country B to avoid the tariff. Enhanced tracking and cooperation between customs and climate authorities internationally will be important.

Addressing equity through adjustment of policy design: The current CBAM has critics, but the EU has room to adjust. One future development to watch is how the EU might use CBAM revenues. There will be political pressure (from the developing world and perhaps progressive voices in the EU) to dedicate some of that money to help poorer countries decarbonize their industries. If that happens, it could make CBAM more palatable globally – reframing it as part of a broader climate finance effort. Another adjustment could be carving out exceptions or longer phase-ins for least-developed countries’ exports, to acknowledge their special status. The EU thus far sticks to a uniform approach, but future negotiations (for example, under WTO or bilateral talks) might lead to tweaks that build more equity into the system without undermining climate goals.

Possible convergence with global carbon pricing: Optimists suggest that CBAM is a stepping stone to a more harmonized global carbon pricing regime. If the major economies all end up pricing carbon (via taxes or ETS) and agreeing to some common rules, the need for border adjustments diminishes. It’s conceivable that in a decade or two, we have a climate club of big emitters with a minimum carbon price, and CBAMs between them are turned off or limited only to outsiders. In that sense, CBAM’s heavy lift might be a temporary bridge toward the end goal of universal carbon costs. Of course, that requires a level of international trust and coordination that is hard to predict. But CBAM has at least thrown down a gauntlet, spurring conversations that were easy to ignore previously. It tells the world: if you don’t price carbon, we will price it for you on entry to our market. That’s a powerful motivator and could accelerate climate policy adoption elsewhere.

Risk of fragmentation: Conversely, one must acknowledge a less sunny scenario too. If poorly handled, CBAM could lead to trade disputes and a fragmented system where each bloc does its own thing in an uncoordinated way. For instance, if the U.S. decided to impose a wildly different carbon tariff and the EU and U.S. didn’t recognize each other’s systems, companies could face multiple charges. That would be inefficient and possibly contentious. The future challenge is ensuring that carbon border measures, if proliferating, move toward coherence rather than chaos. Institutions like the WTO or G7/G20 may become forums to harmonize approaches, set standards, and avoid conflict.

In conclusion of this forward look: carbon border adjustments are likely here to stay in some form, as nations strive to marry climate urgency with economic fairness. The EU’s CBAM is pioneering this path. Its true legacy will depend on whether it manages to spur broader climate action and cooperation. If it does, we might one day see a global economy where the carbon content of goods is as important a factor as their labor or material cost – a fundamental reshaping of global trade for a sustainable future.

Conclusion: Embracing Climate Responsibility in Trade

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism represents a bold step into a new era where climate policy and trade policy intersect. It embodies a simple but powerful principle: the price of goods should reflect their environmental cost. Throughout this article, we explored how CBAM works as a fee on carbon-intensive imports, designed to prevent carbon leakage and support the EU’s climate goals. We discussed its integral role in the EU Green Deal and how it ties into the broader fight against climate change by incentivizing cleaner production worldwide. We also unpacked valid criticisms – from trade partners’ concerns to questions of fairness for developing nations – and saw that CBAM’s implementation will need careful calibration and international dialogue.

Despite the challenges, CBAM signals an important shift. It acknowledges that climate responsibility doesn’t stop at a country’s borders. By adjusting for carbon at the border, the EU is effectively saying that everyone who wants to sell in its market must play a part in the climate solution, or at least not undercut those who do. This is a significant precedent. If successful, it can demonstrate that climate action and competitive markets can go hand in hand, and it may well spark a domino effect of similar policies or encourage a convergence towards global carbon pricing. If it stumbles, it will offer lessons on what to improve in balancing economic and environmental objectives.

As we look to the future, the concept of carbon border adjustments could become a standard feature of international trade, aligning economic incentives with the urgent need to reduce emissions. The road will not be easy – diplomacy, innovation, and cooperation will be needed to refine CBAM and expand its acceptance. But one thing is clear: the conversation around CBAM has already nudged climate change to the forefront of trade discussions worldwide. In that sense, it has succeeded in its fundamental purpose – awakening a new awareness that sustainable practices are not just a moral choice but increasingly a requirement in the global marketplace.

Europe’s CBAM is thus more than an EU policy; it’s a conversation starter for the planet on how we collectively ensure that climate ambition is not a losing game but a shared journey. The coming years will reveal how that journey unfolds, but the destination it strives for is commendable – a world where economic prosperity and environmental sustainability walk hand in hand.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which products and countries are affected by the EU’s CBAM?

A: CBAM initially covers imports of electricity and industrial commodities: specifically iron and steel, cement, fertilizers, aluminum, hydrogen, and some related downstream products. These are sectors with high CO2 emissions. The mechanism applies to imports from all non-EU countries except those with a carbon pricing system deemed equivalent to the EU’s (for example, Norway or Switzerland, which already price carbon similarly, might be exempt). There are no specific country exemptions for developing nations in the current design, meaning major exporters like Russia, China, Turkey, Ukraine, India, and others will be affected to the extent they export the covered goods to Europe. However, if an exporting country has its own carbon price, importers can deduct that cost – so in practice, exporters from countries with climate policies won’t be double charged. Least-developed countries don’t get an exemption, but the EU is exploring support to help them adapt.

Q2: How is the carbon content of an imported product determined?

A: During the transitional phase, importers must report the embedded emissions of their goods – essentially the tons of CO2 emitted in producing them. To determine this, importers will gather data from the producer about fuel usage, electricity consumption, and process emissions. The EU provides detailed methodologies for each product (e.g., how to calculate emissions per ton of steel or cement). If an importer cannot get verified data from the producer, the EU will assign a default value (likely a worst-case estimate based on the most carbon-intensive production). This default is intentionally punitive to encourage real data reporting. In the definitive phase (from 2026), those reported emissions translate into the number of CBAM certificates the importer must purchase. The system may allow third-party verification and audits to ensure the numbers aren’t being gamed. It’s complex, but the idea is to measure as accurately as possible the CO2 footprint of each imported batch. For electricity, it might use the carbon intensity of the exporting country’s grid if specific data isn’t available. As systems improve, we expect more precise tracking (possibly even digital carbon passports for products in the future).

Q3: What will happen to the money collected from CBAM certificates?

A: The revenue from CBAM will go into the EU budget, at least initially. The EU has proposed that part of CBAM revenues be classified as “own resources” to help fund EU programs (notably to help repay the large COVID recovery fund). However, there is an ongoing debate on the best use of this money. Many argue it should support climate action, especially in poorer countries. For example, it could be invested in green technology transfers or funding renewable energy projects in developing trading partners – this would address fairness concerns and help those countries lower their emissions (reducing future CBAM liabilities). As of now, the legislation doesn’t earmark the funds for external climate finance, but pressure is mounting to do so. It’s possible that in the future the EU will allocate a portion to assist vulnerable countries or domestic climate transition efforts. Transparency on revenue use will be important to the CBAM narrative – the more it’s seen as re-invested in sustainability, the easier it may be to accept internationally.

Q4: How does CBAM relate to the WTO rules – can other countries legally challenge it?

A: CBAM sits at the intersection of trade law and climate policy, which is relatively untested. WTO rules forbid discriminatory tariffs (you generally can’t tax the same product differently based on origin). The EU has tried to design CBAM to be origin-neutral and based only on objective emissions content, treating domestic and foreign carbon equally. In principle, this aligns with WTO provisions that allow border adjustments for things like taxes – and potentially for environmental measures under certain exceptions (like Article XX for environmental protection). However, it’s likely that some country might bring a WTO dispute to challenge CBAM’s consistency with trade law. The outcome would set a crucial precedent. If WTO blesses CBAM, it opens the door for others to do similar measures. If it strikes it down, then the EU would have to adjust the policy (or negotiate a special climate trade solution). Some legal experts think CBAM can be justified under WTO rules if done right, especially since it mirrors costs internal EU producers face (so it’s about equalizing conditions). But we won’t know for sure until it’s tested. In any case, the EU is engaging diplomatically to try to avoid legal fights – for instance, by offering technical dialogues and perhaps agreeing on mutual recognition if other countries implement their own carbon pricing.

Q5: Will CBAM increase costs for consumers and businesses in the EU?

A: In the short term, the direct impact on EU consumer prices is expected to be modest for most goods, because CBAM targets basic materials rather than finished consumer products. You might see a slight increase in the cost of things like construction materials (steel, cement) or possibly downstream products like appliances or cars insofar as their production involves imported high-carbon steel or aluminum. For businesses that rely on imported raw materials, CBAM does mean higher input costs if those imports are carbon-intensive. They will either have to switch suppliers, press suppliers to reduce emissions, or pay the certificate costs. In aggregate, studies have suggested the effect on inflation will be very small initially, especially during the transition period when no actual payments occur. Over time, if carbon prices rise further, there could be more noticeable impacts on certain sectors (e.g., construction, machinery, fertilizers could affect agriculture costs). The idea, however, is that domestic producers already face these carbon costs under the EU ETS – so CBAM is making sure importers face the same costs rather than giving them a free ride. Consumers might actually see a more level playing field where low-carbon products become competitive. It’s also possible that innovation spurred by CBAM will lead to cheaper low-carbon alternatives in the long run. So while there may be some cost passthrough, the overall goal is to minimize it by encouraging efficiency and ensuring no one is disadvantaged for doing the right thing on climate. The European Commission’s analysis suggests CBAM’s impact on EU price levels will be minor, but we’ll have to watch the data once it’s fully operational. In any case, the cost of inaction – climate change – would be far higher, which is part of the rationale for accepting these adjustments now.