Table of Contents

ToggleUnpacking the Basics: What Exactly is CBAM?

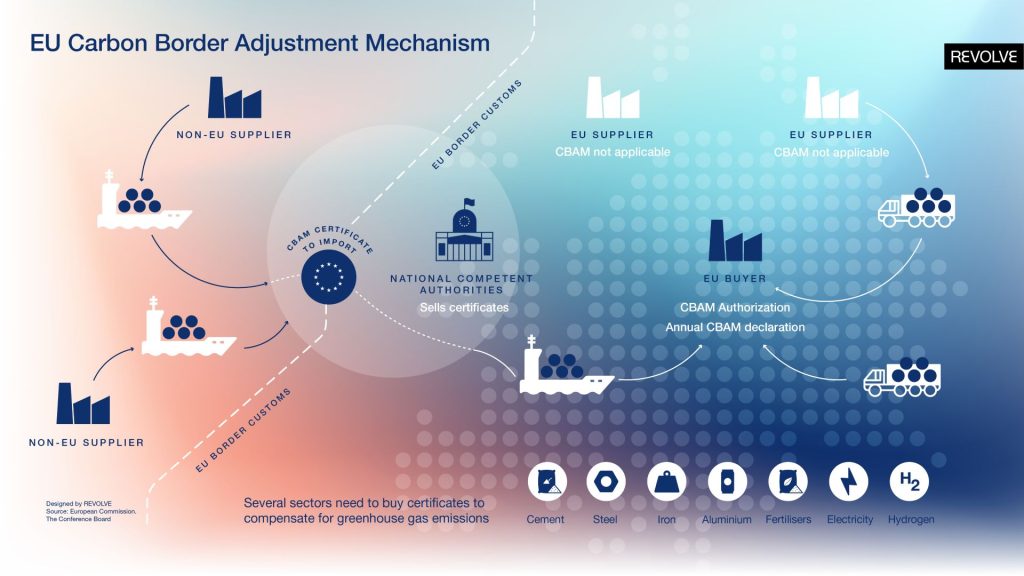

Defining CBAM: A Fee for Carbon-Intensive Imports A Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), sometimes referred to as a Carbon Border Adjustment Tax (CBAT), can be understood as a fee or tariff applied to goods imported from outside a specific economic zone. This charge isn’t arbitrary; instead, it’s directly linked to the quantity of greenhouse gases emitted during the production of those goods. Essentially, it’s a way of accounting for the carbon footprint of imported products at the border. This mechanism aims to level the playing field between domestic producers, who often face carbon pricing or stricter environmental regulations, and foreign producers who might not.

This approach marks a significant evolution in how international trade interacts with environmental policy. It suggests a move towards incorporating the environmental costs associated with manufacturing into the price of goods, irrespective of their origin. By doing so, CBAM seeks to address a critical gap in current trade practices, where the environmental impact of production in one country may not be reflected in the cost of goods consumed in another.

The Core Objectives: Leveling the Playing Field and Reducing Emissions The primary aim of a CBAM is two-fold: to reduce emissions that contribute to global warming and to encourage cleaner production processes on a global scale. Goods manufactured in countries with less stringent emissions standards often have a lower production cost but result in higher greenhouse gas emissions. This situation can create an unfair competitive advantage for these producers and potentially lead to what is known as carbon leakage.

To counter this, the EU’s CBAM has several key objectives. These include ensuring a **fair price on the carbon emitted** during the production of carbon-intensive goods entering the EU, incentivizing **cleaner industrial production** in non-EU countries, effectively **preventing carbon leakage**, supporting the ongoing **decarbonization of EU industries**, and ensuring that the mechanism operates in a manner **compatible with the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO)**.[4] By putting a price on the carbon content of imports, CBAM aims to eliminate the cost advantage enjoyed by producers in regions with lax environmental regulations, thereby promoting a more level playing field for businesses operating under stricter climate policies.

The EU’s Pioneering Initiative: CBAM Implementation in Action

Current Status and Timeline: From Transition to Definitive Phase The European Union took a significant step by formally adopting the CBAM regulation on May 17, 2023. Currently, the initiative is in its transitional phase, which commenced on October 1, 2023, and will continue until December 31, 2025. This initial period is primarily focused on data collection and the refinement of methodologies for calculating embedded emissions. Importers of goods falling under the CBAM scope are now required to report on the greenhouse gas emissions associated with their imports on a quarterly basis, but no financial adjustments, such as the purchase of certificates, are yet required.

The **definitive period** of CBAM is scheduled to begin in **January 2026**.[4, 5, 6] From this point forward, importers will be obligated to **submit yearly reports** on their imported goods, along with **verified data on the emissions** embedded in their production.[4, 5] Crucially, they will also need to **purchase CBAM certificates** corresponding to these declared emissions.[4, 6] The price of these certificates will be linked to the price of carbon allowances within the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS).[8, 9] This implementation timeline is also strategically aligned with the **gradual phasing out of the free allocation of emission allowances** to EU industries under the ETS, a process that will occur between 2026 and 2034.[5, 10]

Sectors Initially in Scope: Focusing on High-Risk Industries The EU has strategically chosen to initially apply CBAM to sectors identified as being both carbon-intensive and at the highest risk of carbon leakage. These sectors include cement, iron and steel, aluminum, fertilizers, electricity, and hydrogen. By focusing on these key industries, the EU aims to address a significant portion of the emissions covered by its existing ETS – estimated to be more than 50%. This targeted approach allows for a more manageable initial implementation and focuses on the sectors where the potential for emissions reduction and the risk of carbon leakage are most pronounced.

Furthermore, the EU has indicated that the scope of CBAM may expand in the future to include other carbon-intensive products, such as **chemicals and refinery products**.[10] This suggests that businesses in these potentially future sectors should proactively begin assessing their carbon footprints and supply chains to prepare for potential inclusion in the CBAM framework.

Why CBAM? The Rationale Behind the Carbon Border Adjustment

- Tackling Climate Change: A Global Responsibility The fundamental rationale behind CBAM is the urgent need to combat climate change, a challenge that requires global cooperation and action. The EU’s implementation of CBAM is a clear signal of its commitment to its ambitious climate goals and an attempt to encourage similar ambition and action from its trading partners. By ensuring that imports meet comparable environmental standards to those imposed on domestic producers, the EU hopes to drive a worldwide shift towards greener production practices and ultimately contribute to a significant reduction in global greenhouse gas emissions. This initiative reflects a growing recognition that climate change is a global problem that necessitates international collaboration and that trade can be a powerful mechanism to promote environmental sustainability.

- Preventing Carbon Leakage: Keeping Production Clean A primary driver for the implementation of CBAM is the need to prevent carbon leakage. Carbon leakage occurs when businesses, faced with carbon pricing or stricter environmental regulations in one region, decide to relocate their production to countries with less stringent rules to avoid these costs. This not only undermines the climate efforts of the region with stricter policies but also does little to reduce overall global emissions. CBAM aims to address this issue by imposing a carbon cost on imports, effectively leveling the playing field and removing the incentive for businesses to simply shift their polluting activities to other parts of the world. This is particularly important for the EU as it phases out the free allocation of emission allowances under its ETS , which previously helped its industries compete with producers in regions without carbon pricing.

How CBAM Works: The Nitty-Gritty Details

- Covered Sectors: A Closer Look at Who’s Included The application of CBAM is not a broad, industry-wide measure but rather targets specific goods within the initially selected sectors, identified by their Combined Nomenclature (CN) codes. For example, in the aluminum sector, this includes unwrought aluminum, powders, flakes, bars, rods, profiles, wire, plates, sheets, strip, foil, tubes, pipes, and certain other articles. However, more complex aluminum products, such as car doors, are currently excluded. Similarly, for iron and steel, the coverage spans from raw materials like agglomerated iron ores to primary forms like pig iron and spiegeleisen, and extends to various finished products including flat-rolled products, bars, rods, and structural shapes. Cement includes cement clinkers and different types of hydraulic cements, including Portland and aluminous cement. The fertilizers category covers a range of nitrogenous fertilizers, nitric acid, and other mineral or chemical fertilizers. Finally, electricity (CN code 2716 00 00) and hydrogen (CN code 2804 10 000) are also included. This specific targeting based on CN codes ensures that the mechanism focuses on goods with a high risk of carbon leakage and allows for a more precise application of the carbon adjustment.

- Calculating Embedded Emissions: Measuring the Carbon Footprint A core element of CBAM is the requirement for importers to report the greenhouse gas emissions that were released during the production of the goods they import. These emissions are categorized as both direct emissions, which occur directly from the production process, and indirect emissions, which are associated with the consumption of electricity, heating, or cooling used in the production. During the current transitional phase (October 2023 to December 2025), importers have some flexibility in how they calculate and report these embedded emissions. Until the end of 2024, companies can choose between full reporting according to the new EU methodology, reporting based on an equivalent method, or using default reference values provided by the European Commission (though the use of default values is only permitted until July 2024).

- However, as the **definitive period** commences in January 2026, the reporting requirements will become more stringent. Importers will primarily be expected to use the **EU’s specific methodology** for calculating embedded emissions.[4, 18] While estimates may still be permitted under certain conditions, particularly for complex goods, the emphasis will be on accuracy and the use of **primary data sourced directly from the producers** of the imported goods.[18, 19] The fundamental approach to calculating emissions involves multiplying the **weight of the imported good (in tonnes)** by an **emission factor**, which represents the quantity of emissions associated with the production of one tonne of that specific good.[18] To ensure consistency and accuracy, the EU’s **Combined Nomenclature (CN) codes** are used to link the imported goods with the appropriate emission factors.[18] This detailed process aims to establish a reliable and transparent system for quantifying the carbon footprint of imported goods.

CBAM in Action: Real-World Examples Across Industries

- Steel Industry: Navigating New Carbon Costs The steel industry is among the first to be subject to the EU’s CBAM. Importers of steel into the EU will be required to account for and potentially pay a price on the embedded carbon emissions generated during its production, mirroring the costs faced by EU steel producers under the ETS. The range of covered products is extensive, spanning from raw materials like iron ores to various finished steel forms. Interestingly, the initial phase of CBAM focuses on relatively simple steel products, excluding more complex manufactured steel items. This new regulation is prompting non-EU steel manufacturers to respond to increasing demands from their EU customers for detailed emissions data. The implementation of CBAM is expected to lead to an increase in the cost of imported steel into the EU. While some major steel-exporting countries might have relatively lower carbon emissions in their production, others, particularly those relying on more carbon-intensive processes, could face significant challenges in maintaining their competitiveness in the EU market.

- Cement Industry: Adapting to Emission Reporting The cement industry is another significant sector within the scope of CBAM. Notably, all types of cement are classified as complex goods under CBAM as they are produced using precursors such as clinker, which is considered a simple good. During the transitional period, both direct and indirect emissions from the production of imported cement and its precursors must be reported in terms of metric tonnes of CO2 equivalent per tonne of output. The reporting requirements vary depending on the specific type of cement and its production process. For instance, the reporting for calcined clay production differs from that of cement clinker or finished cement. Exporters of cement products to the EU are required to register their installations and submit quarterly reports detailing their greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, they must also provide information on the clinker content of the cement being exported. The implementation of CBAM is expected to incentivize the adoption of lower-carbon production methods and alternative fuels within the cement industry.

- Aluminum Industry: Addressing Energy-Intensive Production The aluminum industry, known for its energy-intensive production processes, is also subject to CBAM. Importers of aluminum into the EU will need to declare and potentially purchase CBAM certificates to cover the greenhouse gas emissions associated with its production. A key aspect of the discussion surrounding aluminum has been the potential inclusion of indirect emissions, particularly those arising from the electricity consumed during production. During the transitional phase, non-EU aluminum producers are required to provide data on both direct and indirect emissions. While the responsibility for CBAM compliance primarily rests with the importer, non-EU producers will need to provide the necessary emissions data. Similar to steel, the initial phase of CBAM focuses on simpler forms of aluminum, potentially excluding more complex manufactured aluminum goods. The inclusion of indirect emissions in the definitive phase is expected to significantly impact the cost of imported aluminum, especially from countries with carbon-intensive electricity generation.

The Ripple Effect: CBAM’s Impact on International Trade

- Implications for Developing Countries: Challenges and Opportunities The implementation of CBAM is anticipated to have significant implications for developing countries, particularly those with economies heavily reliant on exports of the carbon-intensive goods covered by the mechanism. These countries may face reduced export volumes to the EU as their products become relatively more expensive due to the carbon levy. Studies suggest that African economies, for instance, could be particularly affected, with potential decreases in exports of aluminum, iron and steel, fertilizers, and cement. This could lead to a reduction in GDP and income in some developing nations. Notably, the current CBAM regulation does not provide exemptions for least developed countries.

- However, amidst these challenges, CBAM also presents potential **opportunities** for developing countries.[9, 15, 31] It could incentivize these nations to **invest in cleaner technologies and adopt more sustainable production methods** to maintain their competitiveness in the EU market and potentially gain access to new markets for low-emission products.[9, 15, 31] The EU has also launched initiatives aimed at providing **technical assistance and financial support** to help developing countries in their transition towards greener economies.[9, 29] Some developing countries might also consider implementing their own carbon pricing mechanisms or export taxes as a response to CBAM.[29]

- Reshaping Global Trade Relationships: New Alliances and Considerations The introduction of CBAM is expected to contribute to a reshaping of global trade relationships. It could foster new trade alliances between countries with similar levels of climate ambition and carbon pricing policies. Some countries are already accelerating their efforts to reduce carbon emissions and are considering implementing domestic carbon pricing systems to maintain their competitive edge in the EU market. Conversely, the implementation of CBAM could also lead to trade tensions with countries that view it as a protectionist measure or that are significantly impacted by its costs. The United Kingdom’s plan to implement its own carbon border adjustment mechanism by 2027 suggests a potential trend towards the adoption of such mechanisms by other developed economies. Overall, CBAM introduces a new dimension to international trade, where the carbon footprint of goods will increasingly become a factor in determining their competitiveness and shaping trade flows.

Navigating the Challenges: Criticisms and Concerns Surrounding CBAM

- Complexity and Administrative Burden: Making it Work A significant concern surrounding CBAM is its inherent complexity and the potential for a substantial administrative burden, particularly for businesses involved in importing goods within its scope. Many stakeholders have expressed worries about the challenges of accurately measuring and reporting the embedded emissions in imported goods, especially given the intricacies of global supply chains. The initial de minimis threshold for CBAM compliance was considered by many to be too low, potentially impacting a large number of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and occasional importers. The process for obtaining authorization as a CBAM declarant has also been criticized for its complexity. In response to these concerns, the European Commission has proposed some simplifications to the regulations, including a new compliance threshold based on the weight of imported goods and a delay in the requirement to purchase CBAM certificates. The EU is also providing guidance and training materials to assist businesses in understanding and complying with the new requirements.

- Potential for Protectionism: Fair Trade or Barrier? One of the main criticisms leveled against CBAM is the concern that it could be used as a form of protectionism, unfairly disadvantaging imports from certain countries. Some trading partners, including major players like China, have labeled CBAM as a trade barrier that could potentially violate the principles of non-discrimination under the World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. The EU, however, maintains that CBAM is a legitimate environmental measure designed to prevent carbon leakage and ensure a level playing field for its domestic industries, which already face carbon pricing through the EU ETS. The fact that EU producers have historically received free allowances under the ETS, which are only being phased out gradually in conjunction with the introduction of CBAM , is a point of contention for some critics who argue that this provides a temporary advantage to EU industries. The design and implementation of CBAM will be crucial in determining its compatibility with WTO regulations and in mitigating the risk of trade disputes.

CBAM’s Wider Reach: Implications Across Domains

- Environmental Policy: Driving Global Green Standards CBAM has the potential to significantly influence environmental policy on a global scale by encouraging countries outside the EU to adopt more ambitious climate policies and cleaner production methods. By placing a carbon cost on imports, the EU is essentially creating an economic incentive for exporting countries to implement their own carbon pricing mechanisms or regulations aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This could lead to a broader global convergence on carbon pricing and contribute to a more effective international effort to combat climate change. The EU hopes that CBAM will not only prevent the relocation of polluting industries but also inspire a worldwide movement towards greener industrial practices.

- Economics: Shifting Markets and Incentivizing Innovation Economically, CBAM is expected to lead to shifts in global trade patterns. There could be a decrease in demand for carbon-intensive goods from countries with weak environmental regulations and a corresponding increase in demand for products from countries with lower carbon footprints. This shift in demand is likely to incentivize innovation in green technologies as companies strive to reduce their carbon emissions to maintain or enhance their competitiveness in the EU market and potentially other markets that might adopt similar measures. While the implementation of CBAM might lead to short-term price increases for some consumers , the long-term economic benefits of a transition towards a more sustainable, low-carbon economy are expected to be substantial.

- International Law: Ensuring Compliance and Avoiding Disputes From the perspective of international law, a key consideration for CBAM is its compatibility with the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO). While some legal scholars argue that a well-designed carbon border adjustment mechanism can be consistent with WTO principles, particularly if it treats domestic and imported goods in a non-discriminatory manner , other countries have expressed concerns and there remains a risk of trade disputes and legal challenges as CBAM is implemented. Ensuring that CBAM adheres to the principles of non-discrimination and national treatment under WTO law will be crucial for its long-term viability and global acceptance.

- The Future of CBAM: Potential for Adoption in Other Regions While the EU is the first major economy to implement CBAM, it is unlikely to be the last. Several other regions and countries are actively considering or planning to introduce similar mechanisms. The United Kingdom has announced its intention to implement its own CBAM by 2027, closely mirroring the EU’s approach in terms of the sectors covered. Countries like Australia, Canada, and Turkey have also reportedly been exploring the possibility of adopting carbon border adjustments. Even in the United States, there has been growing discussion and the introduction of legislative proposals for CBAM-like policies. The experience of the EU with its pioneering CBAM initiative will undoubtedly provide valuable lessons and influence the design and adoption of similar mechanisms in other regions around the world.

Conclusion: Embracing the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism for a Sustainable World

In conclusion, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) represents a significant and ambitious step towards aligning international trade with climate objectives. By placing a carbon cost on imports from regions with less stringent environmental regulations, the EU aims to prevent carbon leakage, encourage cleaner global production, and ensure a level playing field for its domestic industries. While the implementation of CBAM presents considerable challenges, including administrative complexities and the potential for trade tensions, its underlying rationale – to internalize the environmental costs of carbon emissions in the price of goods – is a crucial element in the global transition towards a more sustainable future. The EU’s pioneering effort is being closely observed by other nations, and its success will likely influence the broader adoption of carbon border adjustment mechanisms as a key tool in the fight against climate change.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What is the main goal of CBAM? The primary goal of CBAM is to put a fair price on the carbon emitted during the production of certain goods imported into the EU. This aims to encourage cleaner production in non-EU countries and prevent carbon leakage, ensuring that the EU’s climate objectives are not undermined.

- When does the definitive phase of EU CBAM begin? The definitive phase of the EU CBAM, when importers will be required to purchase CBAM certificates, begins in January 2026.

- Which industries are initially covered by CBAM? The industries initially covered by CBAM are cement, iron and steel, aluminum, fertilizers, electricity, and hydrogen.

- How will CBAM affect developing countries? CBAM could lead to reduced exports to the EU and potential GDP losses for developing countries, particularly those with carbon-intensive industries. However, it also presents an opportunity to transition to cleaner production methods and access new markets for greener products. The EU is providing some assistance to support this transition.

- Is CBAM considered a form of protectionism? Some countries view CBAM as a form of protectionism, arguing that it creates trade barriers and unfairly targets imports. The EU maintains that it is a legitimate environmental measure designed to prevent carbon leakage and ensure a level playing field for its industries. The compatibility of CBAM with WTO rules is still a subject of debate.

Table: EU CBAM Implementation Timeline

| Phase | Date | Description |

| Adoption | May 17, 2023 | The EU formally adopts the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism regulation. |

| Transitional Phase (Reporting Only) | October 1, 2023 – December 31, 2025 | Importers of covered goods are required to report the embedded greenhouse gas emissions associated with their imports on a quarterly basis. No financial adjustments (payment for certificates) are required during this phase. |

| Definitive Phase (Financial Adjustments Begin) | January 1, 2026 | Importers will start to purchase and surrender CBAM certificates corresponding to the embedded emissions of their imported goods. The price of these certificates will be linked to the price of carbon allowances in the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS). |

| Phase-out of Free EU ETS Allowances | 2026 – 2034 | The free allocation of emission allowances under the EU ETS for sectors covered by CBAM will be gradually phased out. This means that EU producers will also face the full carbon price, ensuring a level playing field with importers subject to CBAM. |

Table: Sectors Initially Covered by EU CBAM

| Sector | Description |

| Cement | Includes cement clinkers and various types of cement (e.g., Portland cement, aluminous cement). |

| Iron and Steel | Covers a wide range of iron and steel products, including raw materials, semi-finished products, and finished goods like flat-rolled products, bars, rods, and wire. |

| Aluminum | Includes unwrought aluminum, aluminum powders and flakes, and various aluminum products such as bars, rods, profiles, wire, plates, sheets, tubes, and pipes. |

| Fertilizers | Covers nitrogenous fertilizers, including ammonia, nitric acid, and mineral or chemical fertilizers. |

| Electricity | All electrical energy imported into the EU. |

| Hydrogen | Hydrogen gas. |